Atlantic World > War and Marshall Aid

- A country in motion

- The Marshall Aid

- Reasons for emigration

- From Bos en Lommer to Quang Tri, by way of Minnesota

- Rock and Roll in Tulip Country

Een land in beweging

Peace

On 8 May 1945, the Allied and German army commanders agreed to an armistice on the Lüneburg Heath in Germany. For the first time since long the cannons were silent and survivors could think once more about their future.

As a result of the hostilities, millions of people in Europe were uprooted. Former prisoners of war, forced labourers, concentration camp survivors and civilian refugees took to the roads to go home or to what was left of it.

![]()

What next?

What next?

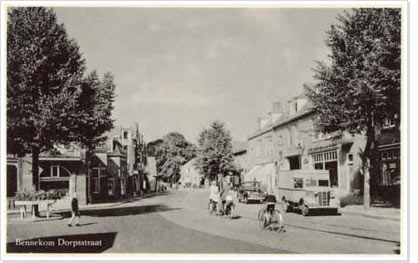

More than nine million people were living in the Netherlands in 1945. Almost one million of them had been forced by the hostilities to leave hearth and home. Around 220,000 Dutch people had lost their lives during the war. Large parts of the infrastructure such as factories and companies, bridges and railroads, were destroyed. From the ravaged countryside the cattle had been carried off to Germany. During the first months after the liberation the country was in chaos.

Immediately after the capitulation of the German troops in the Netherlands, 350,000 people who had been in hiding, sometimes for a long period of time, left their hiding places. They were not the only ones who took to the roads. By the end of 1945, almost two million people were on their way to a destination somewhere within the Dutch borders. Most of them were returning from Germany.

Around 300,000 forced labourers, some 12,000 Dutch prisoners of war and more than 20,000 political prisoners left Germany to go home. Almost 50,000 Jewish people returned to the Netherlands from the concentration camps, about one third of the total number of Jews who had been deported. From other European countries, an additional 60,000 Dutch forced labourers came back.

In addition to these vast numbers of people, there were around 120,000 members of the German armed forces who for some reason or other were forced to stay in the Netherlands. Finally, the c. 130,000 Dutch people should be mentioned who for reason of their actual - or alleged - collaboration with the defeated enemy were kept prisoner by the Dutch government.

In addition to these vast numbers of people, there were around 120,000 members of the German armed forces who for some reason or other were forced to stay in the Netherlands. Finally, the c. 130,000 Dutch people should be mentioned who for reason of their actual - or alleged - collaboration with the defeated enemy were kept prisoner by the Dutch government.

![]()

War again

While still in England, the Dutch government in exile had developed plans to liberate the Dutch East Indies immediately upon their return to the Netherlands. Those colonial possessions at the other end of the world had been occupied by Japan since 1942. More than 40,000 Dutch troops and 100,000 Dutch civilians were put in Japanese concentration camps, of whom 8,000 and 16,000 respectively lost their lives. An unknown number of Indonesian civilians met with the same fate.

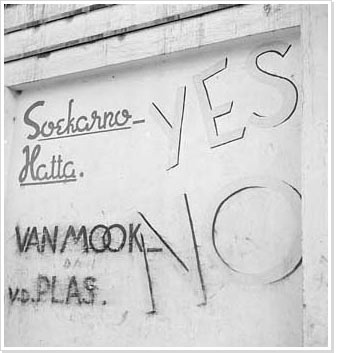

The Japanese capitulation on 15 August 1945 did not immediately bring freedom to the Dutch inhabitants of the archipelago. Indonesian nationalists proclaimed independence on 17 August. It became clear to the government, now once more residing in The Hague, that they would not be able to restore colonial rule in Indonesia without a struggle.

A military response followed in 1947 with the first of two 'Police Actions' that were meant to restore 'peace and order' to the rebellious colony. More than 120,000 troops were sent from the Netherlands to Indonesia. More than 6,000 of them would not return, as a result of the hostilities. It was all in vain. In 1949, under international pressure, the Indonesian independence was finally recognized. The troops returned home, followed by 200,000 Dutch and Dutch-Indonesians, who in a military or civilian capacity had been connected with colonial rule. From 1954 onwards a second large group of Dutch and Dutch-Indonesians followed. More than 45,000 people were forced to leave, or could not see a future for themselves in the new Republic of Indonesia.

A military response followed in 1947 with the first of two 'Police Actions' that were meant to restore 'peace and order' to the rebellious colony. More than 120,000 troops were sent from the Netherlands to Indonesia. More than 6,000 of them would not return, as a result of the hostilities. It was all in vain. In 1949, under international pressure, the Indonesian independence was finally recognized. The troops returned home, followed by 200,000 Dutch and Dutch-Indonesians, who in a military or civilian capacity had been connected with colonial rule. From 1954 onwards a second large group of Dutch and Dutch-Indonesians followed. More than 45,000 people were forced to leave, or could not see a future for themselves in the new Republic of Indonesia.

![]()

Out of the Netherlands

Between 1945 and 1955, 245,103 Dutch people left the Netherlands, that in their view was becoming increasingly overpopulated. 105,023 of them went to Canada, 70,644 to Australia, 22,903 to South Africa, 13,078 to New Zealand and 26,355 people left for the USA. An additional 7.000 emigrants settled in other countries.

The Marshall Aid

Hunger and shortages Another section of this website deals with the socio-economic situation in the Netherlands in the years between 1945 and 1955. Other European countries also faced major socio-economic problems.

Another section of this website deals with the socio-economic situation in the Netherlands in the years between 1945 and 1955. Other European countries also faced major socio-economic problems.

America, Europe's most important trade partner, considered this situation as a cause for anxiety. Up until June 1947, the Americans gave more than nine and a half billion US dollars worth of financial-economical aid to the 'Old World'. This proved to be insufficient and American economists predicted a negative effect on the American trade balance, caused by the slow European recovery. In their opinion, Europe had to invest without delay in their manufacturing capacity to avoid two actual threats. It was possible that Europe would disintegrate further as a result of the communist threat, and because of the lack of foreign currency they would be unable to buy American products.

The vulnerability of the 'Old World' was brought home again when Europe experienced the coldest winter in years, causing many families to suffer from hunger and cold.

An American plan

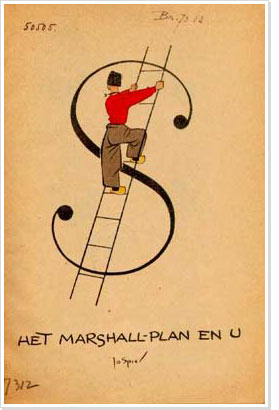

In a speech given at Harvard University, the American Secretary of State George C. Marshall outlined his assistance programme for Europe on 5 June 1947. This plan, formally named the Economic Recovery Program, became known in the Netherlands as Marshall-plan or Marshall-hulp (Marshall Aid). It combined various American financial economic European aid programmes and was meant to replace the existing UNRRA aid programme (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency) that had been set up just after the end of the Second World War under control of the United Nations. Until that moment the US accounted for more than 70% of UNRRA's budget. However, the American government was far from pleased with the course of events regarding the UN Aid and they wanted an aid programme that was far better geared to serve American national interests. The Undersecretary of State, W. Clayton simply stated: 'The United States must run this show!'.

Europe responds

Marshall invited the European countries to draw up a joint aid programme. This had to contain an inventory of the aid that was needed and it had to describe how the recovery of the European economy could be stimulated through improved European co-operation. A condition for the promised aid was that America was willing to assist only countries that guaranteed individual rights and liberties to their citizens. One month later, sixteen European countries met in Paris to draw up the required aid programme. The Soviet Union and a number of its satellite states were absent because of the American conditions. Only with great difficulty and with the help of American observers did the participants succeed in drafting the European Recovery Program (ERP).

![]()

The response of the American Congress At the end of December 1947, the American president Harry S. Truman presented a bill to Congress. To persuade the representatives to support the plan, he emphasized the political objectives the Marshall Aid would support. It could strengthen Europe in its role as: 'a stronghold for the principles of right and liberty and individual dignity against the establishment of the totalitarian state.' The American Congress did not approve the Marshall Aid without ado. They made additional demands and conditions, the most important being that the aid should be provided for the larger part in the form of goods. This meant that the European countries did not receive actual Marshall dollars but help in kind. On 2 April 1948 the bill, now named the Economic Cooperation Act, was passed by Congress and signed the next day by president Truman. In the same year the motor ship Noordam arrived in Rotterdam from America with the first shipment of relief supplies for the Netherlands With the next shipment came surplus goods such as lorries and building machines. Scrapped Liberty and Victory ships, no longer needed to carry American supplies and war materials to Europe, were given a new life as Dutch civilian cargo ships. The Americans also shipped grain, maize and other foodstuffs.

At the end of December 1947, the American president Harry S. Truman presented a bill to Congress. To persuade the representatives to support the plan, he emphasized the political objectives the Marshall Aid would support. It could strengthen Europe in its role as: 'a stronghold for the principles of right and liberty and individual dignity against the establishment of the totalitarian state.' The American Congress did not approve the Marshall Aid without ado. They made additional demands and conditions, the most important being that the aid should be provided for the larger part in the form of goods. This meant that the European countries did not receive actual Marshall dollars but help in kind. On 2 April 1948 the bill, now named the Economic Cooperation Act, was passed by Congress and signed the next day by president Truman. In the same year the motor ship Noordam arrived in Rotterdam from America with the first shipment of relief supplies for the Netherlands With the next shipment came surplus goods such as lorries and building machines. Scrapped Liberty and Victory ships, no longer needed to carry American supplies and war materials to Europe, were given a new life as Dutch civilian cargo ships. The Americans also shipped grain, maize and other foodstuffs.

![]()

Reduction Over a four year period, the Netherlands were given around one billion American dollars worth of relief goods. Only a minor part of this astronomical figure was provided in the form of loans, the major part consisted of donations.

Over a four year period, the Netherlands were given around one billion American dollars worth of relief goods. Only a minor part of this astronomical figure was provided in the form of loans, the major part consisted of donations.

After 1952 the nature of the American aid to Europe changed and the Marshall Aid was gradually reduced. It was replaced by the Mutual Defence Assistance Act (MDAA). The Mutual Security Agency (MSA) saw to it that economic aid to European countries was strictly connected to military expenditure. The Netherlands, by then a member of NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation), got the newest American army equipment, naval vessels and fighter planes at their disposal via the MDAP (Mutual Defence Assistance Program).

Reasons for emigration

A wave of emigration In the course of the nineteenth century, an estimated 100,000 Dutch people left for the United States of North America, 9,517 people in the peak year 1882. Those are impressive figures for that era but insignificant compared to the period from 1945 until 1955, the years that saw the largest emigration wave in Dutch history.

In the course of the nineteenth century, an estimated 100,000 Dutch people left for the United States of North America, 9,517 people in the peak year 1882. Those are impressive figures for that era but insignificant compared to the period from 1945 until 1955, the years that saw the largest emigration wave in Dutch history.

When in 1955 the final count was taken, 245,000 Dutchmen turned out to have left the country, most of them never to return. In the peak year 1952 no less than 48,690 men, women and children departed.

What made so many people leave hearth and home? From the information available to us and the existing literature, it does not prove possible to deduce one single, predominant reason for departure. Often a combination of circumstances formed the incentive for emigration. These circumstances varied greatly and are described here in random order.

![]()

Emigration directly related to the war

Among the first to leave the Netherlands were the so-called 'war brides': women who had started a relationship with liberation army soldiers. Because the Canadian army played a major role in the Dutch liberation, most of the c. 2000 female emigrants in this category departed for that country.

Secondly, there were the men who during their military service or training abroad got involved with women in the country were they were stationed. The circumstances in the Netherlands being what they were, most of these couples chose to stay in the woman's country of origin.

Finally, there was the group of Jews who survived the concentrations camps or spent the war in hiding. Most of the emigrants from this group departed for the United States were many of them had family. From 1948 onwards, Dutch Jews also left for the newly founded state of Israel.

Housing shortage

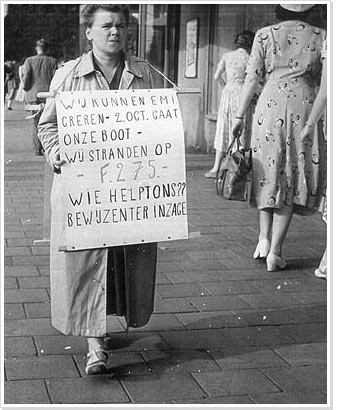

After the war an important part of the housing stock appeared to be seriously damaged. During the occupation no new houses were built. Because of these combined factors, it was almost impossible for people who returned to the Netherlands or who wanted to get married, to find housing. This housing shortage would last until the nineteen seventies.

Many newlyweds were forced to live in with family, friends or other private families. The lack of privacy and the sharing of toilet and bath facilities caused inconvenience and could easily lead to friction. A survey carried out in 1946 and 1947, showed that no less than 42% of the population had housing problems.

![]()

The social situation of the average citizen

The Dutch economy was severely damaged by the war. A large part of the infrastructure that had to support the renewed production of goods and services had been destroyed. Because of the shortage of foreign currency, it was hard for entrepreneurs to buy spare parts or other materials abroad.

The government was forced to introduce a socio-economic policy of frugality. Priority was given to reconstruction of the production facilities. Domestic consumption was of secondary importance. Wages were frozen for a long period of time or were allowed to rise only slightly. The combination of this 'planned incomes policy' and the rationing of various consumer goods that was continued for a considerable period of time after the war, would deny the Dutch population any kind of luxury for some time to come.

![]()

Holland is overpopulated

In 1946 and 1947, just after the war, the Netherlands faced two extensive baby booms. In the same period, large groups of Dutch people from the Dutch East Indies returned to the mother country.  Many people held the view that the fast increase in population growth could in the longer term lead to a new period of mass unemployment.

Many people held the view that the fast increase in population growth could in the longer term lead to a new period of mass unemployment.

To avoid this problem, the government combined their industrialisation policy with an emigration policy. The Queen's speech of 1950 still reported that: "the fast population growth and the limited area of land available continue to demand that emigration is strongly promoted." The government did not stop at putting it into words but established the Nederlandse Emigratiedienst (Dutch Emigration Service), that actively promoted emigration. Apart from the neutral Emigration Service, organisations based on a religious or political ideology were established for the same purpose.

B.P. Hofstede concluded in his large-scale study of Dutch emigration (1964) that for a number of years it was a "mass-psychological phenomenon", something we would now call a 'hype'. As of 1953 the emigration flow gradually declined.

![]()

The political situation After 1945, the world faced a new political situation with two political systems vying for the lead: the capitalist system of the United States and their allies and the communist system of the Soviet Union and its allies. The tensions caused by the continuous confrontation between both systems is known as the period of the 'Cold War'.

After 1945, the world faced a new political situation with two political systems vying for the lead: the capitalist system of the United States and their allies and the communist system of the Soviet Union and its allies. The tensions caused by the continuous confrontation between both systems is known as the period of the 'Cold War'.

This bipolar world manifested itself in particular in Europe were conflicts arose over the communists assuming power in Eastern Europe while at the same time threatening to take over in Greece and Italy. Also outside the 'Old World' tensions arose, over the recognition of Communist China and the control of the Suez Canal.

The Cold War became hot when war broke out in Korea between the communist North and the capitalist South. Both superpowers were directly and actively involved in the conflict. At the same time they were taking part in an arms race, trying to develop the largest and most powerful nuclear weapons.

To many Dutch people it seemed as if another world war could break out in Europe at any moment. This was another reason to emigrate to regions that in all probability would not turn into future battlegrounds.

Van Bos en Lommer naar Quang Tri, via Minnesota

In 1950, almost 3000 people emigrated from the Netherlands to the United States of America, the Blanksma family among them.

War survivor

Gerrit Blanksma, his wife Saartje and their daughters Antonia and Nelly survived the horrors of the German occupation of the Netherlands during the Second World War relatively unscathed. However, they felt increasingly uncomfortable in Dutch post-war society. Although they did not suffer from acute hunger or extreme poverty it was all too clear to father Blanksma that the economic situation in the Netherlands would not improve very soon. The loss of a job and the threat of unemployment were daily experiences for many families in the neighbourhood. On top of this there was the looming possibility of another world war, due to the increasing influence of the Soviet Union in European affairs.

No wonder that the Blanksma's started to think about finding a more prosperous future elsewhere in the world. That idea was not completely alien to them. When Gerrit and Saartje married in the late thirties, they planned to emigrate to America. Relatives had already settled in South Dakota and had invited them in their letters to come over. However, when they tried to do so, they were not admitted into the US because of the so-called quota system. The Dutch allotment of people admitted to the USA for that year had already been reached. The outbreak of the Second World War prevented another attempt.

![]()

To America

Their son, who was also named Gerrit, was born on June 13th, 1946 in their modest apartment in the Juliana van Stolbergstraat in Amsterdam. The neighbourhood at that time was modern and populated by skilled labourers, office people and civil servants. Father Blanksma now started to work on his emigration plans in earnest. Once again fate was not kind to him and his family. This time the United States were in the middle of the McCarthy era bringing with it a very restricted admittance policy for new immigrants. The fact that during the war - like so many Dutchmen - Blanksma had worked for the Germans, formed a barrier to entry. Fortunately, he was somehow able to prove that he had also been involved in the Dutch resistance and had helped downed American pilots to escape. At long last the Blanksma family was granted permission to enter the US. They left Amsterdam by train and boat in the fall of 1950. By way of the port of Southampton in Great Britain they sailed to New York aboard the enormous ocean liner Queen Elisabeth.

Their son, who was also named Gerrit, was born on June 13th, 1946 in their modest apartment in the Juliana van Stolbergstraat in Amsterdam. The neighbourhood at that time was modern and populated by skilled labourers, office people and civil servants. Father Blanksma now started to work on his emigration plans in earnest. Once again fate was not kind to him and his family. This time the United States were in the middle of the McCarthy era bringing with it a very restricted admittance policy for new immigrants. The fact that during the war - like so many Dutchmen - Blanksma had worked for the Germans, formed a barrier to entry. Fortunately, he was somehow able to prove that he had also been involved in the Dutch resistance and had helped downed American pilots to escape. At long last the Blanksma family was granted permission to enter the US. They left Amsterdam by train and boat in the fall of 1950. By way of the port of Southampton in Great Britain they sailed to New York aboard the enormous ocean liner Queen Elisabeth.

Their daughter Antonia still remembers the long hours on the train, seated on hard wooded benches, on their way from New York to Milbank, South Dakota. Two years later the family moved from Milbank to Pequot Lakes, Minnesota, where Blanksma senior started his own carpentry business. The family became American citizens in the 1960's. At that time young Gerrit took his middle name Lynn.

![]()

A Dutch-American Gerrit attended Minnesota Schools and graduated. From there he went to Junior College in Brainerd and on to the University of Minnesota. Gerrit wanted to become an architect. In addition to school, he worked with neighbourhood kids at the YMCA, picking them up after school to play baseball. In fact his life did not differ from that of many other young Americans who were looking forward to bright futures.

Gerrit attended Minnesota Schools and graduated. From there he went to Junior College in Brainerd and on to the University of Minnesota. Gerrit wanted to become an architect. In addition to school, he worked with neighbourhood kids at the YMCA, picking them up after school to play baseball. In fact his life did not differ from that of many other young Americans who were looking forward to bright futures.

In the summer of 1967, Gerrit was drafted into the military. On the other side of the world, the Vietnam War was dragging on and demanding ever more American service personnel. It was also a period of fierce protests against the war. Draft cards were burned publicly during huge demonstrations and quite a lot of draftees tried to evade military service in Vietnam. Some of these evaders (among them a future American president) moved abroad; some of them ended up in Canada, only a few miles from where Gerrit lived. Some draftees were able to fulfil their military service by serving in the National Guard (among them another future American president).

Gerrit even had an extra option to avoid the draft. Without too many problems he could have re-emigrated to his country of origin, that was sometimes swamped by anti-Vietnam War protesters and where he would have been warmly welcomed.

![]()

Into the war Gerrit, however, chose to do what he considered to be his duty. Without much ado he went to Army boot camp and received his training. Just before he was sent overseas, he had a five-day leave period. He went back to his old hometown in civilian clothes. Wearing the uniform of the country he wanted to serve was out of the question. Soldiers were spat on in the streets and in general were treated badly by bystanders and demonstrators alike. When she saw him again, his sister Antonia was under the impression that somehow he already knew that he would not return from the war. He had his will drawn up and gave away his personal belongings. When in May 1968, Private First Class Gerrit Lynn Blanksma, A Company, 2nd BN, 5th Cav Regt, 1 Cav Div, arrived in Vietnam, the war was still raging.

Gerrit, however, chose to do what he considered to be his duty. Without much ado he went to Army boot camp and received his training. Just before he was sent overseas, he had a five-day leave period. He went back to his old hometown in civilian clothes. Wearing the uniform of the country he wanted to serve was out of the question. Soldiers were spat on in the streets and in general were treated badly by bystanders and demonstrators alike. When she saw him again, his sister Antonia was under the impression that somehow he already knew that he would not return from the war. He had his will drawn up and gave away his personal belongings. When in May 1968, Private First Class Gerrit Lynn Blanksma, A Company, 2nd BN, 5th Cav Regt, 1 Cav Div, arrived in Vietnam, the war was still raging.

Six months before, in December 1967, President Lyndon. B. Johnson had declared optimistically that: "All the challenges have been met. The enemy is not beaten but he knows that he has met his master in the field". A month later, on 30 and 31 January 1968, the enemy, in order to meet that master, came out of hiding and launched the Tet-offensive. TV-broadcasts brought the attacks on American and South Vietnamese positions live into the living rooms of America. The shocking sight of general Luan pointing his gun at the head of a captured Vietcong soldier and pulling the trigger, the faces of American Marines battling in the streets of Hue linger on in our collective memory. The struggle for the cities was a turning point in the war. Although the North Vietnamese and Vietcong military were beaten on the battlefield, they scored a political victory.

On March 31, President Johnson told the American public that he had ordered to stop further attacks on North Vietnam. At the end of his speech he announced that he did not seek the nomination for another term as president. In May, North Vietnamese diplomats arrived in Paris to start formal talks with their American counterparts. Peace was at hand but the war-machine still claimed its victims.

Five days after his arrival in Quang Tri Province, Vietnam, Gerrit Lynn Blanksma went out on patrol with his unit. Shortly after he had taken up the point position of the patrol, he was hit in the head by an enemy bullet. Two days later he died from his wounds in hospital.

His name can be found on Panel 70 W, Row 1 of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC.

Rock 'n Roll in Tulip Country

The late 1950s The oppressive morals that had characterized pre-war Holland quickly started to loose their meaning for the nation's youth in the late fifties. Young people no longer felt guided and inspired by adults alone. Increasingly, other young people served as an example for new role patterns. This became visible in particular in fashion and in the music that soon was to be determined by that new phenomenon: Rock 'n' Roll.

The oppressive morals that had characterized pre-war Holland quickly started to loose their meaning for the nation's youth in the late fifties. Young people no longer felt guided and inspired by adults alone. Increasingly, other young people served as an example for new role patterns. This became visible in particular in fashion and in the music that soon was to be determined by that new phenomenon: Rock 'n' Roll.

Back to the old days?

At first nothing seemed to threaten the Dutch musicians who could be listened to on the radio or rediffusion set. Max van Praag, Eddy Christiani, The Ramblers, Mieke Telkamp, Joop de Knegt, Willy Alberti, the Selvera's, Johny Jordaan or children's choir 'de Leidse Sleuteltjes' (the Leiden Keys) continued in the same old way. Pierre Palla played his endless medleys on the organ of the Tuschinsky Theatre in Amsterdam. The idiosyncratic and slightly peculiar acts of performers such as whistler Jan Tromp or the Kilima Hawaïans were extremely popular. 'Foreign influences', if any, came from Germany where Conny Froboess, Catharina Valente and Freddy Quin were all the rage with their schlagers that were played also in Holland, notwithstanding the complaints of the elder generation 'who had been through the war.'

Americanization?

The increasing affluence enabled more and more families to buy a television set. In 1951 the first television programme was broadcast in the Netherlands. The following year the country numbered 500 television sets, a number that was to grow to one million in 1961. At first, there was only one Dutch channel, with limited broadcasts. Nevertheless, television increasingly influenced the use of leisure and thus the Dutch culture. In a much talked-about broadcast of the satirical programme 'Zo is het toevallig ook nog eens een keer' ('That's the way things happen to be') in 1964, television was presented as a new religion.

The increasing affluence enabled more and more families to buy a television set. In 1951 the first television programme was broadcast in the Netherlands. The following year the country numbered 500 television sets, a number that was to grow to one million in 1961. At first, there was only one Dutch channel, with limited broadcasts. Nevertheless, television increasingly influenced the use of leisure and thus the Dutch culture. In a much talked-about broadcast of the satirical programme 'Zo is het toevallig ook nog eens een keer' ('That's the way things happen to be') in 1964, television was presented as a new religion.

Most of what was on offer daily on the screen originated from American studio's. This was also the case with more and more of the light music played on the radio. These programmes had a large appeal with viewers and listeners, quickly resulting in a gradual 'Americanization' of the entertainment industry. The arrival of the so-called radio pirates such as Veronica (1960) contributed to this development.

Dutch teenagers and even 'twens' (twenty-somethings) bought mopeds, blue jeans and milk shakes. They had (portable) transistor radio's at their disposal, and gramophone record players. Without their parents interfering and with great enthusiasm they listened to American Rock 'n' Roll. It became the thing to do to buy records by Elvis Presley, Bill Haley, Chuck Berry, Pat Boone, or Buddy Holly. In Muziekexpress, established in 1956, or in Tuney Tunes that had been running longer, they read all about their new heroes, their music and their lifestyle.

![]()

Indo-rock Holland developed a Rock 'n' Roll scene of its own, dominated initially by the so-called Indo-Rockers, Dutch-Indonesians who settled in the Netherlands in the nineteen forties and fifties. Even before they arrived in the Netherlands, they had been familiar with the new American music. It was played by these bands at 'Dutch-Indonesian' parties. Initially, the Indo bands played mainly in their own circle, but more and more often they were asked to perform at teenage events or shows. Indo-Rock became renowned in the Netherlands thanks to the performances of The Tielman Brothers, The Black Dynamites, The Hot Jumpers and many other bands. It became a trend that was soon to be imitated by non-Indo bands.

Holland developed a Rock 'n' Roll scene of its own, dominated initially by the so-called Indo-Rockers, Dutch-Indonesians who settled in the Netherlands in the nineteen forties and fifties. Even before they arrived in the Netherlands, they had been familiar with the new American music. It was played by these bands at 'Dutch-Indonesian' parties. Initially, the Indo bands played mainly in their own circle, but more and more often they were asked to perform at teenage events or shows. Indo-Rock became renowned in the Netherlands thanks to the performances of The Tielman Brothers, The Black Dynamites, The Hot Jumpers and many other bands. It became a trend that was soon to be imitated by non-Indo bands.

Rock City The Hague

The Hague must be considered as the home base of the most high-profile Rock 'n' Roll bands in Dutch national pop history. The presence of many Dutch-Indonesians contributed to this city gaining a leading position in the Indo-Rock scene. In their footsteps a large number of native Dutch R&R bands came into being such as René and the Alligators.

In 1960, Tuney Tunes wrote about René Nodelijk, who gave the band its name, that: "he is definitely not a nozem [a Dutch yob or biker], but studies at the music academy". Fortunately, this proved not to be an impediment to the band becoming - in varying formations - one of the best instrumental bands in the Netherlands.

A Rock career

Richard van der Kraats was the band's drummer from 1959 until 1962. Initially they did not earn a lot of money with their concerts. For transport to the venues they used the delivery van that by day was used in the fish business of Van der Kraats' father. In the winter of 1961/1962 the band got the opportunity to play a gig in Germany. At the time that was the highest achievable for a R&R band. The presence of many American troops guaranteed full houses and thus attractive fees.

![]()

René and the Alligators appeared on television for the first time in July 1962, in the TV programme "Nieuwe Oogst" ("New Harvest"). When the band started to record an album in the autumn of 1962, Richard was unable to attend because he was on holiday. They engaged another drummer, Wim Zech, and Richard lost his place. He tried again for a while with the Black Jets, but it proved to be incompatible with family life. He packed in his R&R career to start work in his father's fish business.

René and the Alligators are still playing the circuit on a regular basis (2004).