Atlantic World > The mania

- What is Holland-mania?

- The boy, the finger, the dyke

- The mother of America, a provoking article

- The emergence of the 'Dollar Kings'

- American artists in the Netherlands

- Holland as a brand in 19th-century advertising

- Renewed Holland-Mania?

In the third quarter of the nineteenth century a curious movement came into being in the United States. Its adherents opposed the view that Great Britain had provided the basis for American society. Well-known and less well-known, rich and not so rich Americans maintained that the Dutch Republic, which they endearingly called Holland, was the "mother of America". This was a fundamental change in the history of the United States. The American historian J.L. Motley first expounded this view in 1856, in his book entitled The Rise of the Dutch Republic.

In the third quarter of the nineteenth century a curious movement came into being in the United States. Its adherents opposed the view that Great Britain had provided the basis for American society. Well-known and less well-known, rich and not so rich Americans maintained that the Dutch Republic, which they endearingly called Holland, was the "mother of America". This was a fundamental change in the history of the United States. The American historian J.L. Motley first expounded this view in 1856, in his book entitled The Rise of the Dutch Republic.

This curious episode in American history was to become known as "Holland-Mania". Annette Stott published a book about it in 1998, which drew renewed attention to this phenomenon from both American and Dutch readers (the translation of the book was published in the same year).

The immediate cause for the rise of the movement was the centennial of the United States in 1876. There was every reason to celebrate the centennial in a grand style. The terrors of the American Civil War (1861-1865) were over, slavery was officially abolished and the country was experiencing unprecedented economic growth. Millions of Europeans left 'Old Europe' to build a new life in the 'New World'. This was sufficient reason to look ahead to a bright future. The economic growth of the United States resulted in the country manifesting itself on the world market. There it constituted a threat to the most powerful industrial nation of the world at the time: Great Britain.

Against this background, people in certain circles in America started to look for a new source of social inspiration. These circles consisted mainly of white protestant Americans who had already been in the US for a longer period of time. In general they were reasonably well off. For this group the new influx of mostly catholic and Jewish immigrants posed a direct threat. New immigrants, who where not familiar with the American identity, might perhaps want to introduce in the US views on norms and values from their countries of origin. These needed to be countered by American norms and values. The problem was that it was hard to explain what these norms and values amounted to, and from which source they originated.

That source was found in the cultural and political world of the Republic of the Seven United Provinces, in particular as it had manifested itself during the "Golden Age". Descendants of Dutch immigrants and Americans who felt affinity with them set up study groups. They studied the history of the Republic and published a growing number of scholarly and semi-scholarly papers on Dutch culture.

The interest in and identification with the Netherlands was not focused exclusively on political and social aspects of Dutch history. The workings of Dutch democracy, the States General and the outcomes of the Dutch Revolt (the 80 Years' War) kept inspiring Americans. This was accompanied by an interest in Dutch art and culture. Wealthy American collectors began to buy Dutch seventeenth- and eighteenth-century art on a large scale. Because the supply of authentic Dutch masters was of course limited, the prices went up quickly. Another effect was that American artists (sometimes on commission) started to copy Dutch masters. Not always with the right intentions. Inevitably copies of paintings were sold as the real thing.

American artists also developed their own style, that was strongly influenced by the Dutch masters. To please their prospective buyers, they traveled to Holland to paint. They wanted to become acquainted with the 'Dutch light', and in particular with the Netherlands of the Golden Age. But that did no longer exist. The trekschuit (horse-drawn barge) had since long been replaced by the steam engine. Only in certain areas of the Netherlands time seemed to have stood still. In fishing villages on the coast of what was still the Zuiderzee (later to be closed off from the sea by a dyke, and renamed IJsselmeer), or along the North Sea coast, and occasionally in small towns in the Veluwe region and in the province of Zeeland, with a bit of imagination the atmosphere of the past could still be evoked. These were the locations where communities (six of them all in all) of American artists went to work. They painted Dutch fishermen and farmers in clogs and their wives in lace caps and smocks, in an idyllic style. All these people lived in a peaceful land, flowing with milk and honey, at least in the paintings. The people they depicted always resembled the stereotypes, what Americans took to be 'real Dutch heads'.

During their stay the American artists became acquainted with painters of the "The Hague School", such as Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve, Hendrik Willem Mesdag. These modern Dutch painters in their turn profited from the American interest. Their works too started to disappear quickly to American museums and collectors.

During their stay the American artists became acquainted with painters of the "The Hague School", such as Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve, Hendrik Willem Mesdag. These modern Dutch painters in their turn profited from the American interest. Their works too started to disappear quickly to American museums and collectors.

In addition to the paintings and other forms of pictorial art, novels and children's books appeared in the third quarter of the nineteenth century that were also rooted in Dutch past society. These books described the 'typically Dutch' values such as honesty, sincerity, piety, independence and frugality which were assumed still to be present and correct in the Netherlands at that time.

No wonder that Americans who had money and leisure at their disposal departed for that enchanting little country on the coast of the bleak North Sea as soon as the opportunity presented itself. They wanted to see this wonderful world with their own eyes.

The outbreak of the First World War and the period of shortages and economic recession that followed it, ended the interest in the 'Dutch roots'. Around the year 1920 Holland-Mania was over for good.

The boy, the finger, the dyke

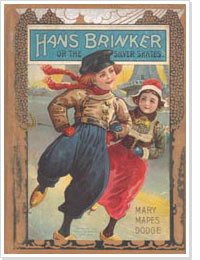

The story of the little boy who averted a flood disaster by sticking his finger in the dyke is famous all over the world . Mary Mapes Dodge (1831 - 1905), an American author of children's books, wrote the story around 1865. It was included in a volume of stories published under the title The silver skates, a story of life in Holland. This book contains various romantic stories about adventures of children in the Netherlands. The pivotal story is that of Hans Brinker, a poor boy about ten years of age, and his younger sister Gretel who try to win an ice skating race. The first price of the race is a pair of silver skates. These they don't wish to keep for themselves but plan to sell. With the money they can buy medicine to cure their sick dad. It is cold and very far and Gretel wins the race and the skates. The boy who stuck his finger in the dyke goes without a name in the book. We are told only that he is about eight years old, that his father is a lockmaster and that the family lives near Haarlem. One day our anonymous hero discovers a leak in the dyke. The dyke is about to burst any moment. The little boy doesn't think twice but sticks his finger in the hole. The water stops flowing.

The story of the little boy who averted a flood disaster by sticking his finger in the dyke is famous all over the world . Mary Mapes Dodge (1831 - 1905), an American author of children's books, wrote the story around 1865. It was included in a volume of stories published under the title The silver skates, a story of life in Holland. This book contains various romantic stories about adventures of children in the Netherlands. The pivotal story is that of Hans Brinker, a poor boy about ten years of age, and his younger sister Gretel who try to win an ice skating race. The first price of the race is a pair of silver skates. These they don't wish to keep for themselves but plan to sell. With the money they can buy medicine to cure their sick dad. It is cold and very far and Gretel wins the race and the skates. The boy who stuck his finger in the dyke goes without a name in the book. We are told only that he is about eight years old, that his father is a lockmaster and that the family lives near Haarlem. One day our anonymous hero discovers a leak in the dyke. The dyke is about to burst any moment. The little boy doesn't think twice but sticks his finger in the hole. The water stops flowing.

There he is, with nobody around to help the little hero. Evening comes and then night falls. It gets colder and colder. Apparently nobody in his family thinks of going to look for the little fellow. The result is that the child, numb with cold, is not found until morning, by the vicar. Now his father and the authorities quickly take action and all ends well. By a curious whim of fate the anonymous hero erroneously became known under the name of Hans Brinker. It was not Mary Mapes Dodge who gave him that name, but unknown readers who couldn't remember the names of the heroes in the book and got them mixed up.

Its writer probably didn't foresee that the story would become such a huge success. It was frequently reissued and adapted. Already in 1867 an adapted Dutch translation appeared of the story about the ice skating race, by P.J. Andriessen, probably the most famous Dutch writer of children's books at the time. It would take another century before the complete original story was published in Dutch.

Its writer probably didn't foresee that the story would become such a huge success. It was frequently reissued and adapted. Already in 1867 an adapted Dutch translation appeared of the story about the ice skating race, by P.J. Andriessen, probably the most famous Dutch writer of children's books at the time. It would take another century before the complete original story was published in Dutch.

When the book was on sale in American bookshops for the first time, there was great interest in the Netherlands. In this period of 'Holland-Mania' numerous American children, who had never been to the Netherlands, became acquainted with Dutch rural life. The writer of the story had never been to the Netherlands either. Although she had done some research into life in that damp little country, she showed a preference for romantic and not always accurate historical information. The image that Mary depicted of the Netherlands did not correspond with reality. But that didn't matter at all. It made the book even more attractive to many readers.

The National Library of the Netherlands has recently (2004) received a very special collection of children's books. Hendrik Edelman was looking for a suitable location and decided to donate his carefully built-up collection to KB. Edelman was born in the Netherlands but moved to America in 1967, where he worked as a librarian, bibliographer and book historian.

The mother of America, a provoking article

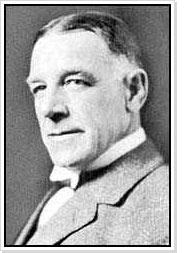

Last summer around 20,000 American tourists visited the Netherlands, Edward Bok wrote in 1904 in an article entitled: The mother of America. He placed this massive interest for the Netherlands in a wider perspective. That the interest in all things Dutch had developed at a mad pace in recent years had a reason. More and more Americans 'discovered' that the roots of American society were not located in Great Britain but in the Netherlands. Aspects such as the freedom of the press, the freedom to practice the religion of one's choice, the system of free public education and secret elections were seen as important criteria in this respect. These were all achievements that in the colonial period had not existed in Great Britain. That they were nevertheless introduced by British colonists was because so many of the Pilgrim Fathers, as some of the early colonists were called, had spent some time in the Netherlands. There they had become acquainted with these influential ideas which they brought with them to America. Even the most important documents from the history of the US, the Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution were derived from comparable earlier Dutch documents. Furthermore, there was the entire catalogue of achievements that could be traced back directly to the institutions of the Dutch Republic, claimed Bok, who therefore in his article posed the question which should be called the mother of America: Great Britain or the Netherlands? With this he more or less followed in the footsteps of the man who some ten years before, in 1891, had stated the same thing in a lecture. That lecture was entitled The influence of the Netherlands in the making of the English commonwealth and the American Republic. The speaker, William Elliot Griffiths, published his ideas three years after his lecture in a booklet entitled: Brave little Holland and what she taught us. Bok was therefore not the first who defended this provoking claim. His influence was nevertheless a lot greater than Griffiths'.

Last summer around 20,000 American tourists visited the Netherlands, Edward Bok wrote in 1904 in an article entitled: The mother of America. He placed this massive interest for the Netherlands in a wider perspective. That the interest in all things Dutch had developed at a mad pace in recent years had a reason. More and more Americans 'discovered' that the roots of American society were not located in Great Britain but in the Netherlands. Aspects such as the freedom of the press, the freedom to practice the religion of one's choice, the system of free public education and secret elections were seen as important criteria in this respect. These were all achievements that in the colonial period had not existed in Great Britain. That they were nevertheless introduced by British colonists was because so many of the Pilgrim Fathers, as some of the early colonists were called, had spent some time in the Netherlands. There they had become acquainted with these influential ideas which they brought with them to America. Even the most important documents from the history of the US, the Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution were derived from comparable earlier Dutch documents. Furthermore, there was the entire catalogue of achievements that could be traced back directly to the institutions of the Dutch Republic, claimed Bok, who therefore in his article posed the question which should be called the mother of America: Great Britain or the Netherlands? With this he more or less followed in the footsteps of the man who some ten years before, in 1891, had stated the same thing in a lecture. That lecture was entitled The influence of the Netherlands in the making of the English commonwealth and the American Republic. The speaker, William Elliot Griffiths, published his ideas three years after his lecture in a booklet entitled: Brave little Holland and what she taught us. Bok was therefore not the first who defended this provoking claim. His influence was nevertheless a lot greater than Griffiths'.

As a seven-year-old Dutch immigrant, Edward W. Bok arrived in 1870 with his parents in New York. Six years later, in the centennial year of the United States, the family were accepted as citizens in their new homeland. By working hard and marrying well (he married the publisher's daughter) Bok became editor in chief of the leading women's magazine "Ladies' Home Journal", a position he was to fill for thirty years. He succeeded in making the magazine the largest and most important of its kind. With its circulation of more than one million copies it left its competitors far behind. In his book The Model Man, writer Hans Krabbendam describes the great influence of the journal on the education of millions of American middle class women. During this period they went through the transition from Victorian to more modern views. In that process the opinions of the editor in chief played an important role.

The emergence of the 'Dollar Kings'

In Dutch newspapers they were sometimes called Dollar Kings: the American millionaires who had amassed large fortunes during the last quarter of the nineteenth century by investing in railroads, shipping lines, oil or steel. Part of their wealth they spent on paintings, drawings, prints and other art forms. At first, the art works were displayed in the magnificent villas they had erected for themselves. When these villas became too small to house their expanding collections, they supported the building of museums where all their treasures could be shown to the public. In particular in the big cities on the east coast prominent art museums were established.

In Dutch newspapers they were sometimes called Dollar Kings: the American millionaires who had amassed large fortunes during the last quarter of the nineteenth century by investing in railroads, shipping lines, oil or steel. Part of their wealth they spent on paintings, drawings, prints and other art forms. At first, the art works were displayed in the magnificent villas they had erected for themselves. When these villas became too small to house their expanding collections, they supported the building of museums where all their treasures could be shown to the public. In particular in the big cities on the east coast prominent art museums were established.

The American collectors' passion was focused mainly on the European market. The short history of the young state had not yielded fifteenth-, sixteenth-, or seventeenth-century American masters. These masters were only to be found in Europe. Agents of American collectors searched the European art market. In particular the seventeenth-century Dutch masters aroused the desire of the nouveaux riches. Soon, hardly any art works of any significance were to be found on the old continent. As soon as an art work appeared on the market, Americans seized their chances and another European cultural artefact disappeared to the other side of the ocean.

One Dutch newspaper wrote, somewhat bitterly, that it would soon be impossible to organise a decent exhibition of Dutch masters. To see them one would have to go to America!

In Nederland schreef een krant enigszins zuur dat het weldra onmogelijk zou zijn om een behoorlijke tentoonstelling van Hollandse meesters te organiseren. Om die te zien moest men eerst naar Amerika!

American artists in the Netherlands

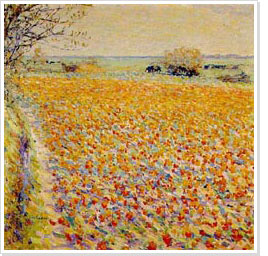

From the beginning of the nineteenth century foreign artists visited the Netherlands. They came to study the famous "Dutch Masters" such as Rembrandt, Van Ruisdael, Hals, Vermeer and Cuyp in the museums, and to work with the renowned "Dutch light". Polder landscapes, town views, the life of farmers and fishermen, preferably in traditional costume and against a backdrop of windmills and bulb fields, were immortalized on canvas and in sketchbooks.

From the beginning of the nineteenth century foreign artists visited the Netherlands. They came to study the famous "Dutch Masters" such as Rembrandt, Van Ruisdael, Hals, Vermeer and Cuyp in the museums, and to work with the renowned "Dutch light". Polder landscapes, town views, the life of farmers and fishermen, preferably in traditional costume and against a backdrop of windmills and bulb fields, were immortalized on canvas and in sketchbooks.

Although the seventeenth-century Holland that the artists were looking for as their subject did not exist anymore, the consequences of the emerging industrialisation were still limited. Only in a few regions the landscape had been radically altered. In some parts of the country one could still effortlessly imagine oneself in the past century.

Most artists were European, but more and more Americans started to arrive as well. They were drawn by the descriptions by American and European travellers who had visited 'Rembrandt's country' before them. The French artist and writer Henri Havard, for instance, wrote a book entitled: La Hollande Pittoresque, voyage aux villes mortes du Zuiderzee. In this book he described his journey, the landscape and the inhabitants of the 'dead villages' along the Zuiderzee. It became a huge success, also in English translation.

Most artists were European, but more and more Americans started to arrive as well. They were drawn by the descriptions by American and European travellers who had visited 'Rembrandt's country' before them. The French artist and writer Henri Havard, for instance, wrote a book entitled: La Hollande Pittoresque, voyage aux villes mortes du Zuiderzee. In this book he described his journey, the landscape and the inhabitants of the 'dead villages' along the Zuiderzee. It became a huge success, also in English translation.

In the same period, the American William Elliot Griffis wrote The American in Holland: sentimental rambles in the eleven provinces of the Netherlands.

The praise of the Netherlands was not only sung in books. In America articles were published about the Dutch wonderland in various weeklies and monthlies. Often the readers of these magazines could buy cheap reproductions of the paintings and drawings described in their pages. Culture was no longer exclusively available to the elite, the middle classes now also had access to cultural products.

The enthusiasm of the American artists who visited the Netherlands, and of the buyers of their works in America, was great. Artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler, George Hitchcock, William Henry Howe, Joseph Raphael, Elisabeth Nourse and many others established themselves for a longer or shorter period of time in the 'picturesque environment' of their choice. Locations such as the fishing villages Volendam, Marken, Edam, Scheveningen or Egmond were seen as unique in the world. In and around the Veluwe region American artists descended; in Laren (province of North Holland) and Nunspeet, and in the province of Zeeland too they took to work.

The enthusiasm of the American artists who visited the Netherlands, and of the buyers of their works in America, was great. Artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler, George Hitchcock, William Henry Howe, Joseph Raphael, Elisabeth Nourse and many others established themselves for a longer or shorter period of time in the 'picturesque environment' of their choice. Locations such as the fishing villages Volendam, Marken, Edam, Scheveningen or Egmond were seen as unique in the world. In and around the Veluwe region American artists descended; in Laren (province of North Holland) and Nunspeet, and in the province of Zeeland too they took to work.

Often they worked in 'seventeenth century Dutch style'. The inhabitants of towns and villages served as models or sources of inspiration. They were painted in detail and 'from life'. Some artist lived in one place for years, others returned every summer for renewed inspiration.

Wherever foreign artists settled, a tourism infrastructure would develop almost automatically. Local entrepreneurs capitalized on the needs of the artists and their guest for lodgings, food and drink. In some places, such as Volendam (Spaander) and Laren (Hamdorff), establishments were set up that are still offering hospitality today. They also profited from the tourists who appeared in the wake of the artists. These were people who wanted to see the colourful world depicted by the artists with their own eyes.

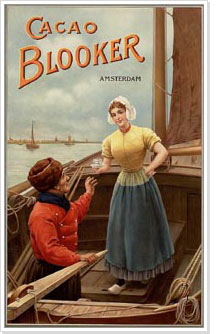

Holland as a brand in 19th century advertising

In the period known as 'Holland-Mania', American trade and industry gratefully used the market value of the word and the concept of 'Holland'. Nineteenth-century American writers, travellers and artists who had been there helped to give this concept its attractive connotations. From their reports and their imagination an image was born that even today stimulates the American fantasy.

In the period known as 'Holland-Mania', American trade and industry gratefully used the market value of the word and the concept of 'Holland'. Nineteenth-century American writers, travellers and artists who had been there helped to give this concept its attractive connotations. From their reports and their imagination an image was born that even today stimulates the American fantasy.

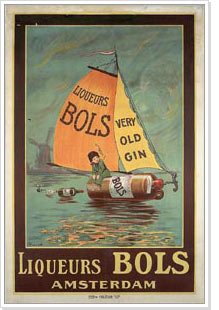

This image consisted mostly of clean-washed, tough, pipe-smoking Volendam fishermen or rural characters from the Veluwe (in the east of the country). The depicted imaginary Dutchmen were put in a landscape full of cows, tulips and windmills. Thus they developed into icons of cleanliness, solidity and reliability. These in particular were the concepts that had to make cleaning products, cacao, alcoholic beverages etc. attractive to American consumers.

On packaging and in adverts 'typically Dutch' images started to appear, even when there was only a very weak link between the product and the depicted scene. In an advert for elegant ladies' footwear for instance, a picture of a milkmaid in clogs could be found. Why? Not because clogs were the most comfortable of shoes, but because the fresh, clean and cheerful milkmaid presented such a strong image. An image that the consumer would easily remember.

The gin distillery of Erven Lucas Bols in Amsterdam made use of the fact that in 1575 their first production facilities were located on Rozengracht (a canal in Amsterdam). Believe it or not, but the famous painter Rembrandt once had a studio on that very same canal, the distiller announced. Thus suggesting that the quality of their product was comparable with that of their 'neighbour' Rembrandt.

The gin distillery of Erven Lucas Bols in Amsterdam made use of the fact that in 1575 their first production facilities were located on Rozengracht (a canal in Amsterdam). Believe it or not, but the famous painter Rembrandt once had a studio on that very same canal, the distiller announced. Thus suggesting that the quality of their product was comparable with that of their 'neighbour' Rembrandt.

Renewed Holland-mania?

In the nineteen-twenties the American interest in the Netherlands slackened. Holland-Mania faded away. Fortunately, the interest in the small country on the North Sea did not disappear completely. In the interbellum period for instance, children's books with a typically Dutch character appeared on the American market.

In the nineteen-twenties the American interest in the Netherlands slackened. Holland-Mania faded away. Fortunately, the interest in the small country on the North Sea did not disappear completely. In the interbellum period for instance, children's books with a typically Dutch character appeared on the American market.

In traditional Dutch immigrant regions such as Michigan and New York, some interest in the old country of origin was kept alive. In Michigan, Hope College located in the town of Holland and Calvin College in Grand Rapids both maintained the ties with the Netherlands. See also: www.hope.edu and www.calvin.edu.

In Albany, in New York State, Dr Charles Gehring in 1974 started the New Netherland Project. Gehring graduated in Germanic languages and took his doctoral degree on the use of the Dutch language in colonial New York. See also: www.nnp.org. The project was developed under responsibility of the New York State Library and the Holland Society in New York. It aimed to transcribe, translate and eventually publish as many original seventeenth century documents as possible concerning the early history of New York.

In fact this was the continuation of a project started in the nineteenth century when, commissioned by New York State, an 'agent' was sent to the Netherlands, London and Paris to search the archives for documents about the history of the state. In the mid-nineteenth century this agent, John Romeyn Brodhead, spent a lot of time in the National Archives in The Hague. There he had clerks make copies of documents concerning the early history of New Netherland and New Amsterdam. E.B. O'Callaghan translated Brodhead's findings into English. The results of their work are still being used today in research into Dutch-American history.

In recent years various books have been published, both in America and in the Netherlands, on Dutch-American history. Lately two much discussed novels about New-Amsterdam appeared. Beverly Swerling wrote City of Dreams: A Novel of Nieuw Amsterdam and Early Manhattan. Russel Shorto published The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of the Forgotten Colony That Shaped America.

Recently Janny Venema, who has been working on the New Netherland Project for twenty years, took her doctoral degree on a thesis entitled: Beverwijck: A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652-1664.

The conclusion seems to be justified that, even if there is no question of renewed Holland-Mania, the 'old Holland' on the other side of the ocean has not yet been forgotten.