Atlantic World > Dutch emigration in the 19th century

- Emigration to North America

- Emigration for religious reasons

- From here to there

- Looking for a place to live

- Little house on the prairie

Emigration to North America

The beginning

Dutch people settled in North America from 1624 onwards. When in 1664 the English captured New Amsterdam and the colony of New Netherland, the influx of new groups of Dutch people to the continent came to a halt. This did not change until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Why emigrate? An important motive to emigrate at that time were the adverse economical conditions in the home country. The Napoleonic Wars had left the country exhausted. The Secession War with Belgium, the burden of taxation, the potato blight of 1845-47 and the drought that followed it resulted in high food prices, causing grinding poverty in large parts of the country. The working classes in particular had a hard time of it. Even so, there was yet another reason to leave.

An important motive to emigrate at that time were the adverse economical conditions in the home country. The Napoleonic Wars had left the country exhausted. The Secession War with Belgium, the burden of taxation, the potato blight of 1845-47 and the drought that followed it resulted in high food prices, causing grinding poverty in large parts of the country. The working classes in particular had a hard time of it. Even so, there was yet another reason to leave.

From 1816 onwards, various government regulations were introduced that had a bearing on religious life. As a response to the government's intervention, a movement developed within the Dutch Reformed Church, pleading for a return to more orthodox beliefs. This resulted in the group's secession form the Dutch Reformed Church. They decided to leave the Netherlands and settle in new communities in America. These communities in the American Midwest exerted a great appeal on the relatives left behind in the home country.

![]()

Numbers of migrants The size of the stream of emigrants to the New World did not depend exclusively on the situation in the Netherlands. The prospects in America played an important role as well. The outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the attendant economic crisis immediately resulted in a drop in emigration. On the other hand, the Homestead Act of 1862, promising cheap land to immigrants, revived interest.

The size of the stream of emigrants to the New World did not depend exclusively on the situation in the Netherlands. The prospects in America played an important role as well. The outbreak of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the attendant economic crisis immediately resulted in a drop in emigration. On the other hand, the Homestead Act of 1862, promising cheap land to immigrants, revived interest.

The exact number of Dutch emigrants leaving for North America in the nineteenth century is unclear. Registers of emigrants in the country of origin as well as in the destination country are incomplete and not very well-organized. Robert P. Swieringa calculated that in the period from 1835 until 1880 between 75,000 and 100,000 Dutchmen arrived in their new home country. The peak occurred in the eighteen-eighties. These are considerable numbers seen from a Dutch perspective, though compared with the total of c. 10 million Europeans arriving in the US during the same period, the Dutch share is not very impressive.

Emigration for religious reasons

A conflict about religious doctrine

In 1814, article 133 was included in the first Constitution of the United Netherlands, stating: "The Christian Reformed Religion is that of the Sovereign." The article was removed in 1815 when predominantly Roman-Catholic Belgium became part of the Kingdom. Nevertheless, what is now called the Dutch Reformed Church remained the only recognized protestant denomination in the Netherlands for a long period of time. All governing members of the House of Orange were and still are members of this church.

King William I also occupied himself with religious issues. He ordered rules governing church life to be drawn up for the Dutch Reformed Church. On 7 January 1816 these rules, the General Regulations for the Government of the Reformed Church, were approved by Royal Decree. Many protestants saw this as direct interference in their church affairs.

After 1816, more government regulations followed that affected church life. The schooling and examining of ministers, for instance, were brought under state supervision.

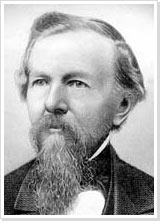

The Secession At the theological faculty in Leiden a group of students actively opposed the government regulations. They found their leader in Hendrik Pieter Scholte. Also after they had graduated and had been appointed as ministers, the group kept in touch and continued their opposition collectively. Among the students were future leaders of emigrant groups such as Albertus Christiaan van Raalte and Anthonie van Brummelkamp.

At the theological faculty in Leiden a group of students actively opposed the government regulations. They found their leader in Hendrik Pieter Scholte. Also after they had graduated and had been appointed as ministers, the group kept in touch and continued their opposition collectively. Among the students were future leaders of emigrant groups such as Albertus Christiaan van Raalte and Anthonie van Brummelkamp.

The struggle against the enforced reformation and for the right to remain orthodox broke out after 1834, when minister Hendrick de Cock from Ulrum together with his congregation publicly seceded from the Reformed Church. In a solemn meeting the faithful signed 'the Act of Secession and Return'. Their example was soon followed by many congregations, including those of Van Raalte and Scholte.

![]()

Ministers in revolt

The Dutch government tried to force the secessionists back into the bosom of the Reformed Church. This was done through a special interpretation of the Constitution, by stating that the freedom of religion, included in the Constitution of 1814, applied only to existing denominations. This made it impossible for the secessionists to appeal to the Constitution. When this did not produce the desired outcome, the government proceeded to dig up some old articles from de Code Napoleon, in particular those articles specifying that to organise and hold meetings of more than twenty people, government permission was required. Referring to these articles the police could legally swoop down on church services on a regular basis and arrest the ministers and their followers.

After the abdication of King William I (1840) the persecution diminished, and even came to a complete stop after 1848, when a new Constitution was introduced. Nevertheless, for many secessionists this came too late. They had already decided to leave the oppressive conditions in the Netherlands behind them. They wished to establish new communities and found that America offered the most favourable opportunities for this. They were supported and inspired in their aspirations by a brochure entitled: 'Why do we promote emigration to North America and not to Java?'. In this brochure Van Raalte and Brummelkamp justified their choice.

To realize their ideals the two militant ministers founded the 'Christian Society for Emigrants to the United States of North America'.

![]()

In search of freedom

The adverse economic conditions in the Netherlands helped to remove any doubts people might still have had about trying their luck elsewhere. In some cases part of a local congregation decided to book their passage, embark and leave for America together. In this way the ministers hoped to prevent the faithful becoming 'distracted'. By acting collectively they could, once they had arrived at their destination, support each other and hear the Gospel together in their mother tongue.

This was a variant on the old Dutch proverb 'eendracht maakt macht' (Union is Strength).

Thus the ministers' followers settled closely together in the states of the Midwest. Even to date Dutch sounding family names and place-names bear witness to this.

The secessionists did not make up the majority of migrants leaving in the nineteenth century. Most of the c. 100.000 migrants trying their luck in America during this period were not involved in the church secession. They dispersed, with or without their families, across the vast continent and merged into the immigrant society.

From here to there

Flying high above the Atlantic Ocean, it is hard for a modern traveller on his way to America to imagine how people crossed the ocean one hundred and fifty years ago.

Emigrants in the nineteenth century crossed the ocean under often atrocious conditions. Nevertheless, millions of Europeans left for the New World, more than one hundred thousand of them from the Netherlands.

![]()

From country to coast Dutch emigrants came from various (often poor) rural areas. It was not easy to scrape together the money needed for the crossing. Sometimes they had to sell their few shabby possessions. People kept only their clothes and some bare necessities. Then the journey started and the emigrants had to take leave, often for good, from their familiar surroundings. Later in the course of the century, financing departure was to become easier because money could be borrowed from relatives that had gone ahead.

Dutch emigrants came from various (often poor) rural areas. It was not easy to scrape together the money needed for the crossing. Sometimes they had to sell their few shabby possessions. People kept only their clothes and some bare necessities. Then the journey started and the emigrants had to take leave, often for good, from their familiar surroundings. Later in the course of the century, financing departure was to become easier because money could be borrowed from relatives that had gone ahead.

The emigrants travelled on foot, by horse-drawn cart, tow barge, regular barge service or train to the ports of Rotterdam or Amsterdam. Some people departed from foreign ports such as Antwerp, Bremen, Liverpool or Le Havre.

There were travel agents who could arrange the entire trip, but not everybody made use of their services. This meant one had to search the harbour for a suitable and affordable ship, which was not always immediately available. During the period that the crossing to America was made exclusively by sailing vessel, once a ship was found one often had to wait for a favourable wind. With the introduction of steamers in the mid-nineteenth century this cause of delay was removed.

![]()

Life on board

As soon as they had embarked, the emigrants could prepare themselves for the journey. Depending on the wind and the season the crossing would take between five and eight weeks. Conditions on board immigrant ships were extremely unpleasant for 3rd class passengers (also called between-decks passengers) and for the so-called 'migrant class' or steerage passengers. The space assigned to people on board was small, dark and often dirty. Most passengers had never even seen the sea and became fearful at the sight of the vast water masses. The food distributed on board was an additional assault on the stomachs of the unhappy travellers. Some passengers spent the entire journey (sea)sick in their beds.

When the journey started in autumn there was a good chance there would be a heavy storm. From stories of passengers and ship's logs we know that when the weather was rough the entrances to the passenger accommodations on board sailing vessels were closed off. The wretched migrants would sometimes have to stay in semidarkness on the lower deck for days on end, in the belly of the rolling, pitching and yawing ship, without the possibility to go on deck and breath in some fresh sea air. The excrement and vomit of the seasick was kept in open barrels. Sometimes these had insufficient capacity, in which case the foul smelling mixture would gush back and forth on the deck of the accommodation quarters with the movements of the ship. Drinking water was transported in wooden barrels at the time. When the journey took long, it had to be diluted with vinegar to stop decay. This could not prevent the water from starting to smell horrible after a while.

Regularly contagious diseases broke out on board. Therefore, not every passenger that had gone on board would reach his or her destination. In most cases this was New York, but some people arrived in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston or New Orleans.

![]()

In America

In their place of entry, the immigrants could make use of the services of official organisations, ministers or individuals who would help them on their way. Inevitably, some of these were impostors and con men. In general though, the immigrants were soon able to continue their journey to their ultimate destination. That was just as well, as is shown by a letter an emigrant from New York wrote to his relatives: This city in many places is very dangerous to pedestrians because of the many carts and wagons and the noise of the many people moving to and fro.

In addition, there was the danger that pious migrants in this city, that even back then 'never slept', would stray from the right religious path.

![]()

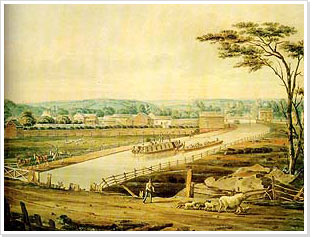

Onwards In America a long journey was often still awaiting the migrants to their ultimate destination. Departing from New York, they travelled onward by American tow barge (called canal boat in America) through the Erie Canal, opened in 1825. This canal linked the port of New York with the Great Lakes in the west. One migrant wrote to his relatives who had stayed behind in the Netherlands that 'the journey took very long, although the barge was towed by 2 horses by turns.' Once they had passed through the canal, the migrants awaited a journey by steamer over the Great Lakes to the States of Illinois and Wisconsin or along the Mississippi to Michigan. When the southern port of New Orleans was the place of entry, people travelled on by Mississippi paddle-wheel to Keokuk and from there onwards over land. Transport along the American inland waterways from 1830 onwards had to compete more and more with the American railroads. These were increasingly capable of bringing the immigrants to their destinations fast and cheaply.

In America a long journey was often still awaiting the migrants to their ultimate destination. Departing from New York, they travelled onward by American tow barge (called canal boat in America) through the Erie Canal, opened in 1825. This canal linked the port of New York with the Great Lakes in the west. One migrant wrote to his relatives who had stayed behind in the Netherlands that 'the journey took very long, although the barge was towed by 2 horses by turns.' Once they had passed through the canal, the migrants awaited a journey by steamer over the Great Lakes to the States of Illinois and Wisconsin or along the Mississippi to Michigan. When the southern port of New Orleans was the place of entry, people travelled on by Mississippi paddle-wheel to Keokuk and from there onwards over land. Transport along the American inland waterways from 1830 onwards had to compete more and more with the American railroads. These were increasingly capable of bringing the immigrants to their destinations fast and cheaply.

Looking for a place to live

The approximately one hundred thousand Dutch people who settled in North America during the nineteenth century dispersed across the vast continent. Many immigrants mixed with the immigrants already there and merged into the American immigrant society. The same does not hold for the immigrants who left their home country for religious reasons. They often left the Netherlands as a group and likewise stayed together as a group in America.

Christian enclaves

In America three large groups of dissenting migrants came into being. They were named after the towns of Utrecht and Arnhem and the province of Zeeland and were led by the ministers Hendrik Pieter Scholte, Albertus van Raalte, Marten Ypma and Cornelis van der Meulen respectively.

Van Raalte's group arrived in November 1846 in New York and departed immediately for Wisconsin. The choice for this region was suggested by acquaintances who had travelled ahead and had sent favourable reports about the opportunities for new settlers to those left behind. Unfortunately they were not able to reach their destination right away because of the severe winter. The group decided to stay in Detroit for the winter. There they heard about the opportunities in Michigan. After a scouting expedition Van Raalte decided to change their destination and bought a large piece of land in Michigan. As soon as the other members of the group had arrived, they started to cultivate the land and founded the town of Holland. Soon afterwards, other Dutch communities came in to being in the same area. Minister Van der Meulen founded Zeeland in Michigan. The whole region acquired a distinctly Dutch character with names such as Vriesland, Groningen, Noordelos and Harderwyk.

At about the same period, in the Iowa prairie the Utrecht group developed into a community led by minister Scholte. In Marion County Pella was founded, the most important Dutch settlement in the area. Its Biblical name referred to the town where the Christians fled when Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD.

Other groupsApart from the protestant emigrants, catholic Dutch people also departed overseas. These were mostly poor small farmers from the provinces of Brabant and Limburg. They had only a minor share in the emigration stream. A group of catholic Dutch people departed for the State of Wisconsin where they settled in places such as Little Chute and Green Bay.

Other groupsApart from the protestant emigrants, catholic Dutch people also departed overseas. These were mostly poor small farmers from the provinces of Brabant and Limburg. They had only a minor share in the emigration stream. A group of catholic Dutch people departed for the State of Wisconsin where they settled in places such as Little Chute and Green Bay.

Elsewhere on the main routes to the West, for instance in the State of Illinois, Dutch immigrants settled in the period just before the outbreak of the Civil War.

![]()

Stranded?

Not all emigrants travelled on right away to the Midwest or other destinations. Many thousands of them for one reason or another stayed behind in America's East Coast ports. Some had to earn enough money first, after arriving in their new country, to be able to buy land elsewhere. Besides, various kinds of diseases forced travellers to stay on for a longer period of time. By the time the sick had recovered or the necessary money had been earned, some of the family members might have found a job and a place to live, which diminished the necessity to travel on.

Little house on the prairie

It was far from easy. When the emigrants finally arrived at their destination after a long journey, they were often disappointed. In their letters to relatives and friends in the Netherlands they described how they sometimes fell prey to despair. The land they had bought had to be cleared. That meant heavy physical labour including uprooting trees, clearing the stumps and ploughing. Those who could not move in with friends or relatives had to put up housing as well. They used the trunks of the uprooted trees to build log cabins, but in some cases even simpler shelters were built.

It was far from easy. When the emigrants finally arrived at their destination after a long journey, they were often disappointed. In their letters to relatives and friends in the Netherlands they described how they sometimes fell prey to despair. The land they had bought had to be cleared. That meant heavy physical labour including uprooting trees, clearing the stumps and ploughing. Those who could not move in with friends or relatives had to put up housing as well. They used the trunks of the uprooted trees to build log cabins, but in some cases even simpler shelters were built.

Dirk Versteeg, one of the first immigrants to settle in Pella (Iowa), in 1886 described these pioneering days as follows:

Just outside what was then Pella you had "Straw Town". Nobody knew how it got its name, because there was no straw to be seen anywhere. That is where the newcomers stayed, as well as the poor who had no or very little capital. They built sod huts. To build these huts they first dug a hole in the ground of 50 centimetres to one meter deep. The sods obtained in this way were supplemented with sods from elsewhere and they were piled up along the edges of the hole. They made up the walls as well as the roof, and even the chimney was made from the same building blocks. It did not take much time to build such a shelter. Spaces were left open to create a door and windows. Steps were made at the entrance to make it easier to descend. Often they did without a wooden floor and ceiling. The furniture consisted of what they had brought with them or what they had made hastily out of planks. These planks they bought from the water-driven sawmill six miles away.

After some years of ups and downs most shabby housings disappeared. They were replaced by better houses. Some immigrants left their log cabin or sod hut standing as a reminder of the harsh times they had lived through, or used it as a storage room or cowshed.