War Diaries > Historical background

‘If future generations are to realize to the full extent what we as a population are going through and what we are experiencing in this time of war, then it is clear that we will need simple documents: a diary, letters from a laborer forced to go to work in Germany, [...] sermons spoken by a clergyman’.

With these words, Gerrit Bolkestein, Minister of Education, Cultural Affairs and Science with the Dutch government in exile in London, appealed to listeners in the occupied Netherlands to record their everyday experiences on paper. In the evening radio broadcast of Tuesday 28 March 1944, he announced the inception of a ‘major, truly national project’.

A young Jewish girl, Anne Frank, who had gone into hiding in a secret attic on Amsterdam’s Prinsengracht canal, was one of the many who heard Bolkestein's appeal at the time. That night she wrote about her housemates: ‘...of course, everyone rushed for my diary all at once’. She imagined how it would be if she would be able to write a novel about the secret attic later on: ‘the title alone would make people think of a crime novel’.

After the war, Anne Frank’s diary became the best-known egodocument of the occupation period. Still, hundreds of other people also wrote down their everyday experiences: housewives, mayors, shopkeepers, physicians, members of the NSB (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging - National Socialist Movement), soldiers on the Eastern front, prisoners and students.

Radio appeals from the RIOD

Starting in December 1945, radio broadcasts called on the population in the Netherlands to put diaries at the disposal of the RIOD (the present NIOD). Many hundreds of listeners sent in pieces of writing recounting their experiences. In the eyes of managing director Loe de Jong, these ‘diaries, that had been kept without any further intention by countless people, would be able to provide future generations with a correct impression of what ordinary citizens experienced during the war and throughout the years of occupation'. It is precisely because the notes had been committed to paper without any ulterior motive, that the diaries form a truly unique historical source.

Honest and frank

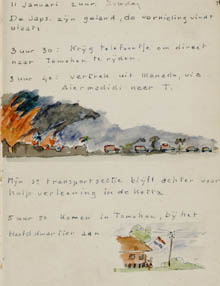

People poured out their hearts in their diaries in all honesty and frankness, like the twenty-year-old secretary musing freely about the outings she goes on with German soldiers and the presents she gets from them. The diaries are also an unexpected source of information for economists and statisticians. Many people were preoccupied by the prices of food and clothing, especially during the Hunger Winter. An Amsterdam housewife exchanges her ‘precious Persian carpet’ for wheat, oil and fish. Major events are sometimes interwoven with personal observations. Around New Year’s Eve 1944, a woman observes that there are almost no skaters on the ice because the men have all been taken away. This finally makes her realize that the Germans have been rounding up the men for forced labor in Germany. The diaries also reflect personal grief; some of them end abruptly because the writer has unexpectedly been arrested or, like the volunteer on the Eastern front, was killed in action.

Writing on cigarette papers

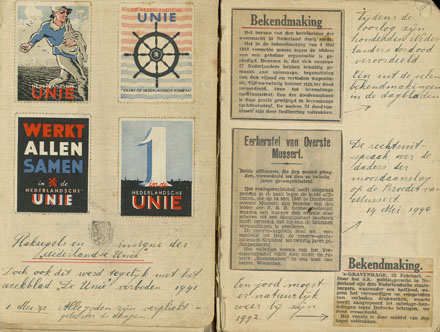

The stories are as varied as the material they are written on. Paper shortages and other circumstances forced people to look for alternatives for notebooks, writing pads, letter paper, or diaries. A Dutch serviceman in Japanese captivity used cigarette papers. Elsewhere in the Netherlands East Indies, someone wrote on the back of monopoly money. Others made drawings or collected newspaper clippings. Every single diary is a unique personal document that belongs to the historical heritage of World War II.

Together, these testimonies form the Nationale Collectie Oorlogsdagboeken (National Collection of War Diaries), which consists of the collections of 20 institutes.