Drawings from the camps in the occupied Dutch East Indies (1942-1945) > Food and health care

In most cases, the Japanese had allowed internees to keep their money and valuables. On the other hand, they expected camp inmates to provide for themselves as much as possible. Most of the time, the Japanese did not issue any rations until the people had used up the greater part of their own means. In the beginning, there was enough food available, but food became increasingly scarce in the course of the war. In 1944 and 1945 there was famine in the camps and among a great part of the native population. Health care deteriorated along the same lines. When the camps were set up, there was no shortage of medical staff. Doctors and dentists had been allowed to bring along part of their instruments, although these were often confiscated later on. Most camps had their own hospital or infirmary, some did not. In the longer term, however, there was a great shortage of medicines and medical equipment.

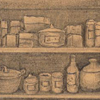

There was a central kitchen in many camps where the rations were prepared, often supplemented with food the camp management had bought in bulk. The big 500-litre drums were about the only part of the camp inventory the Japanese had supplied. Working in the kitchen was exhausting: it began with lighting the fire early in the morning and boiling water for porridge. Other kitchen chores were chopping wood, cleaning vegetables by the hundreds of kilograms and cooking rice. The stock of firewood was supplemented from the houses and barracks with anything that could in any way be missed and would burn. When the meal was ready, it was distributed per house, barrack or shed in portions that had been weighed most precisely. A camp crier announced which part of the camp was next. Long rows of camp inmates stood waiting for their daily portion at the distribution stations. People kept a sharp eye on each other to be sure that nobody got more than they did by accident.

In the beginning, there was a market and a shop in many camps. Quite often, the inmates contributed to a central fund to pay for bulk orders; some of the goods were used in the kitchen, the rest was sold in the camp shop. Everybody was allowed to spend a fixed amount in the shop; the inmates often used special camp money to pay for their purchases. Eventually, the inmates ran out of money and the camp shops were closed.

In many (in due course even in all) camps, the inmates were not allowed to buy more than a limited amount of food from the outside. This resulted in quite a bit of smuggling. Certainly at first, this smuggling involved the guards, who pocketed a commission in return. Sometimes internees managed to sneak away in order to buy things outside the camp, but this became more and more difficult and punishments became increasingly severe as time went by. Smuggling was drastically reduced when the Japanese introduced collective punishment for a single individual’s offence.

Hygiene was poor in the camps. The Japanese seldom handed out toilet paper, soap and cleaning products. In addition, there was not enough water to wash oneself and one’s clothes or to clean the kitchenware. Vermin was another problem. The barracks in the camps were already full of bedbugs when the internees moved in.

The general level of health of the internees declined in the course of the war. In 1943, the first cases of hunger oedema occurred. In 1944 the situation deteriorated rapidly. The major causes for sickness were the increasing lack of food coupled with the hard work the internees were now subjected to, and the ever larger number of people in the camps in combination with the worsening hygiene. Moreover, infections spread easily because of the many transports; the inmates brought contagious deseases along with them when they went from one camp to an other. The number of victims of infections such as diphtheria, dysentery and jaundice increased quickly. Some fifteen percent of the approximately 140,000 internees died.

The Japanese often had a central camp hospital fitted out in camps where the seriously ill were not allowed to go to a free hospital and where a number of camps were in each other’s vicinity,. The hospitals in the larger camps regularly had to be enlarged, at the expense of living accommodations. There were separate wards for children, the chronically ill, dysentery patients and sometimes also for surgical treatment.

There were hardly any medicines, dressings or medical instruments available. Doctors and technicians constructed the missing instruments themselves. Pharmacists and chemists used herbs and other ingredients to compose their own medicines as best they could. They extracted yeast from urine for instance to treat pellagra, an illness caused by vitamin deficiency, In the last year of the war, some medicines from Red Cross shipments reached the camps, although the Japanese withheld the greater part.

Internment in the camps cost thousands of people their lives. Major causes of death were sickness and lack of food. The death rate was more or less normal during 1942 and 1943, but afterwards it increased quickly. For instance in Java, the death rate was three times as high as normal. People who died in the city camps were buried in a public cemetery. Other camps got their own cemeteries. The inmates dug the graves themselves.

>> Read on: Education, religion and leisure

<< Go back to: Life in the camps